Podcast Episode | A Tefillin Tale from Siberia

Release date: 2 November 2023 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

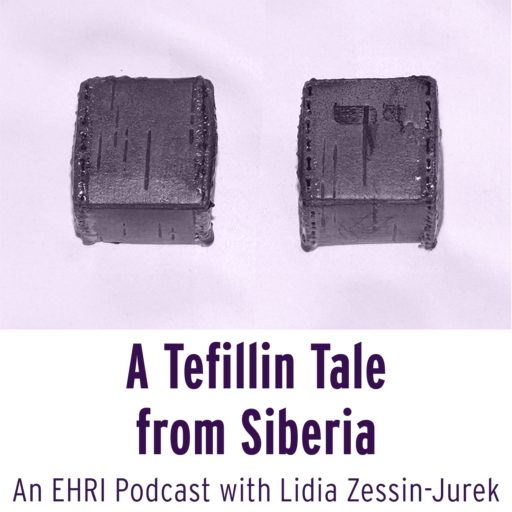

In this episode, Katharina Freise talks with Lidia Zessin-Jurek about some very special tefillin, which is the name given to two black leather boxes with straps which are put on by adult Jews for weekday morning prayers, and are worn on the forehead and upper arm.

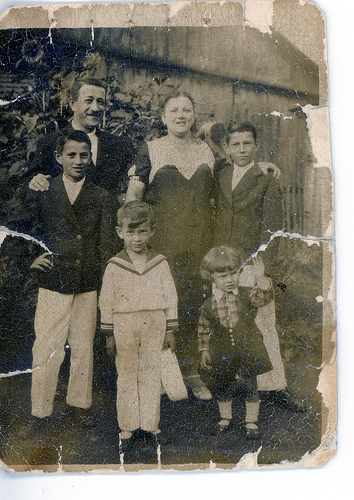

During her research into Polish Jewish refugees in the USSR, Lidia came across the story of the Polaniecki family, mother Frida and father Abram and their four sons (between fifteen and four years old at the time of the war). She got into contact with one of the sons, Salomon (Sam) Polaniecki, who today lives in the US. This Polish-Jewish family fled their home town Brzesko, when Nazi-Germany invaded Poland, and survived the Second World War in the USSR, first in Siberia, later in Tajikistan. Lidia has talked to Sam and his older brother Joseph many times. During their forced exile in the Soviet Union, Joseph made the tefillin of Siberian birch bark. Until 2013, the tefillin were in the possession of the family, the only object, apart from a few photos, they took back with them from the USSR when they returned to Poland after the war. The tefillin are now in the collection of Yad Vashem.

Featured guests:

Lidia Zessin-Jurek is a historian, researcher of memory (Holocaust, Gulag) and refugee movements in Polish lands past and present (refugees on Polish-Belarusian, Polish-Ukrainian borders). As part of an ERC project “Unlikely refuge?” (Czech Academy of Sciences, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Prague), she’s developing a book on the refugeeism of Polish Jews in 1939.

Podcast host is Katharina Freise.

Image top: Birch-bark Tefillin made in Siberia by Joseph Polaniecki (as of 2013 in a deposit of Yad Vashem).

Lidia will tell the story of the Polaniecki family and the tefillin. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or here:

Rodzina Polanieckich / The Family Polaniecki

Nas czterech braci jest na świecie / There’re four of us in the world

Kochamy się tak strasznie, że / Brothers who love each other so

Nie może być brat ani chwili, / That each can’t stand to be

Gdy wkoło nie są bracia mili. / Without the other three.

Gdzie idzie jeden – kroczy trzech, / Where one goes – three will go

To budzi nawet czasem śmiech. / it can indeed be a funny show!

Nie ma drugich takich chwatów / Syr Daria to the Carpathian range

Od Syr Darji do Karpatów. / no one like them, this won’t change.

Cały świat wzdłuż, wszerz przejdziecie / You may travel all way round

Nam podobnym nie znajdziecie. / won’t find second to this crowd.

parents) after their release from

Siberia, in a kolkhoz, 1943

The title of this poem “The Family Polaniecki” – which is recited by Sam in the podcast episode – is a reference to the Noble Prize Winning novel, The Family Polaniecki by Henryk Sienkiewicz. The poem was written in 1945 by the boys’ teacher at a Polish school in Tajikistan, Szeskin, and its protagonists are the four brothers, originating from the little Polish town of Brzesko.

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, many Jews fled to the east, among them our Polaniecki family. With the Soviet Union occupying Poland in the east, they ended up under Soviet rule. The Soviets then deported hundreds of thousands of Poles (including Polish Jewish refugees like the Polanieckis) to Siberia, where they were prisoners and life was extremely harsh.

When Germany broke the nonaggression pact and attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the situation changed and the Polish Jews in Siberia were no longer regarded as prisoners, but ‘free’ to go. Most of them moved south and settled in the Central Asian Republics, also the Polaniecki family. They settled in Leninabad,Tajikistan. There they had to forge a life for themselves, while Russia was at war and Stalin reigned with terror.

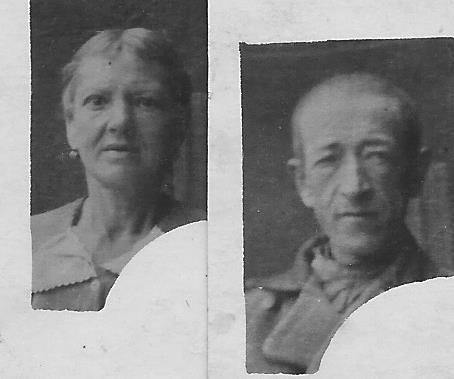

graduating class, Sam Polaniecki

first on the right in the third row from the bottom.

Nevertheless, the whole family survived. After the war, they returned, empty-handed, to Poland, an empty country, in the sense that their homes were gone, but above all the families who had perished in the Holocaust were gone.

After spending several years in Displaced Persons camps in Germany and later in Belgium, Abram and Frida emigrated with their children to the United States, where they tried to build a new life, which was easier for the children than for the father and mother.

Apart from a few photographs from Brzeszko and Tajikistan, the only object that today reminds them of the deportation and the war, the object they returned with and which is featured in this podcast episode, is the tefillin made during the forced exile by the eldest brother Joseph.

Whose Victims and Whose Survivors?

Polish Jewish Refugees between Holocaust and Gulag Memory Cultures

“Hitler killed so many Jews that there is no need to add to his account the Jewish victims of Stalin.” These evocative words were written by Julius Margolin in his gripping, philosophical memoir of surviving WW2. Yet Margolin has never become a household name, in part because he spent his war years as an inmate of the Gulag, not Auschwitz. On September 1, 1939, Margolin, a legal resident of Palestine, was wrapping up affairs in Łódź, Poland, finishing a contract as manager of a textile factory and preparing for publication the second volume of his book about Zionism. Upon the German invasion on September 1, 1939 he fled east—hoping to eventually reach Palestine. The Soviet invasion of Poland from the East on September 17 stopped him, and he was soon sentenced to five years in the Gulag. Having barely survived, in 1946 he returned to Palestine (via Poland) to start writing his memoirs so that the world could learn of all that he had witnessed.

Holocaust and Gulag studies are witnessing the belated emergence of the Soviet experience of Jewish escapees from Nazi-occupied Poland as a lieu de mémoire in its own right. Although not commemorated in official ritual, museum spaces, or memorial sites, the sheer mass of published testimonies by survivors of this experience far outweighs the previous lack of attention to the refugees’ story. It was the agency of the refugee survivors themselves which subsequently put their Soviet experience on the mnemonic map of World War II.

(Leninabad, 1945).

Also the Polaniecki family didn’t talk much about their wartime experiences to the outside world until quite recently. They found themselves in a difficult position. The Holocaust was seen as the bigger suffering, which was understood and accepted by refugee survivors. Also the post-war Soviet domination over Poland and McCarthyism in the 1950’s in the US made that people did not want to be associated with “Russia” so they avoided talking about their “Soviet episode”. Post-1989, Russia was being given “another chance” – so they felt again that coming to terms with the Soviet repression would have to wait. Now this is no longer the case, and people like Sam and Joseph Polaniecki finally start telling their stories.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek

Lidia Zessin-Jurek is a historian, researcher of memory (Holocaust, Gulag) and refugee movements in Polish lands past and present (refugees on Polish-Belarusian, Polish-Ukrainian borders). As part of an ERC project “Unlikely refuge?” (Czech Academy of Sciences, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Prague), she’s developing a book on the refugeeism of Polish Jews in 1939.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek is a historian, researcher of memory (Holocaust, Gulag) and refugee movements in Polish lands past and present (refugees on Polish-Belarusian, Polish-Ukrainian borders). As part of an ERC project “Unlikely refuge?” (Czech Academy of Sciences, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Prague), she’s developing a book on the refugeeism of Polish Jews in 1939.

Together with Katharina Friedla, she published “Syberiada Żydów Polskich” (“The Siberian Odyssey of Polish Jews. The Fate of Holocaust Refugees”, 2020) in Polish and many articles in English on the wartime Soviet survival of Polish Jews, including “Whose Victims and Whose Survivors? Polish Jewish Refugees between Holocaust and Gulag Memory Cultures” in Holocaust and Genocide Studies (2022) and “On a Melting Ice Floe – Polish Jewish Wartime Refugees in Central Asia” in Journal of Genocide Research (2023).

Toward the end of 2023, Brill will publish the refugee memoir A Lost World: the Galician Shtetl and Siberia by Meier Landau under the scholarly editorship of Lidia Zessin-Jurek.

Lidia has been actively involved in EHRI-PP’s Work Package on Sustainability (2019-2023) and was a recipient of the EHRI Conny Kristel Fellowship in 2017.

Learn more

- Lidia Zessin-Jurek, “Whose Victims and Whose Survivors? Polish Jewish Refugees between Holocaust and Gulag Memory Cultures”, in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 36, Issue 2, Fall 2022, Pages 154–170.

- Oral history interview with Joseph Polaniecki USHMM.

- Polaniecki-Epstein family in Brzesko-Briegel Association Memory and Dialogue. Common History.

- Unlikely refuge?

- Lidia Zessin-Jurek as a Conny Kristel Fellow.

- Syberiada Żydów polskich – Introduction in Polish and Abstract in English.

- Lidia Zessin-Jurek’s Introduction to: Yoram Eckstein, An Involuntary Traveler.

- A Lost World: the Galician Shtetl and Siberia by Meier Landau, ed. Lidia Zessin-Jurek.

- Markus Nesselrodt, Dem Holocaust entkommen, De Gruyter 2019

- Eliyana R. Adler, Survival on the Margins, Harvard University Press 2020

- Polish Jews in the Soviet Union (1939–1959): History and Memory of Deportation, Exile, and Survival, eds. Katharina Friedla, Markus Nesselrodt, Academic Studies Press 2021

- Russia in WW2 in the EHRI Portal

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- The Polaniecki family, especially Salomon and Joseph Polaniecki

- Lidia Zessin-Jurek

- Szeskin, author of the poem “Rodzina Polanieckich”. Translation into English: Lidia Zessin-Jurek. English voiceover: Martin Caren

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks – Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14