Podcast Episode | A Message from Malawi

Release date: 03-10-2024 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

Message from Malawi

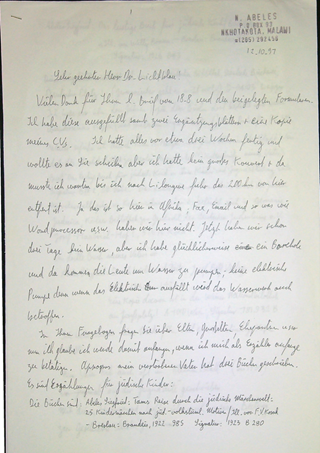

The object of our attention in this episode is a well-travelled letter of 21 pages, received in 1997 by Professor Albert Lichtblau, in response for an appeal for “unpublished biographical memoirs” of Holocaust survivors he had posted on behalf of the Institute for Jewish History of Austria as well as the Leo Baeck Institute in New York. The letter was written by Norbert Abeles, an Austrian living in Malawi, and its arrival prompted an exchange of further letters between Malawi and Austria, unravelling in the process the remarkable story of a young Jewish boy’s escape from Nazi persecution and his journey across three different continents to find home.

Abeles was born in Vienna, Austria in 1923 to Siegfried Abeles, an author of Jewish children’s books, and Sabine Abeles. Abeles’s life was already marred with hardship even before the Nazi occupation of Austria, having experienced the traumatic suicide of his father in 1937, when his mother signed him up for the Kindertransport, an evacuation program for Jewish children in Nazi-controlled countries that took them to the United Kingdom. By the time he said goodbye to her on the platform in December 1938, he already knew it would be the last they ever saw of each other. Indeed, Sabine Abeles was deported to Maly Trostinec on the 6th of May 1942 and was murdered days later on the 11th.

Once in the United Kingdom, Abeles attended Hakhshara, an agricultural school intended to prepare young Jewish people for emigration to Palestine. This school was located in Stenton, East Lothian in Scotland at Whittingehame House, the former home of the Earl of Balfour. The house and the grounds were leased to The Whittingehame Farm School Ltd., a non-profit organisation which aimed to educate and train Jewish children in the range of agricultural skills. Students were instructed in agriculture and horticulture in a combination of English and Hebrew, and days were structured around a half work, half study routine.

Before the end of his time at Whittingehame, Norbert was one of a handful of refugees who were interned as “enemy aliens”. This, along with the trauma of being torn away from their parents and the vastly different backgrounds and beliefs of the children staying at Whittingehame made for turbulent years at the school, which according to Norbert was very much in a “disorganized state”.

After leaving Whittingehame in 1941, Abeles found work as a lock smith’s apprentice whilst attending evening school for a Diploma of the Royal Technical College in Glasgow, which sparked the beginning of a professional career that would take him around the world.

(Norbert Abeles back row extreme right)

Photographer – Farrington Drew.

He married his first wife in 1950, who had also emigrated to the UK from Austria. Together, they left the UK and emigrated to Africa in 1956, living in Nigeria. Norbert would go on to live in different places across Africa, taking various postings in the British Colonial Service, predominantly in the educational department and taking posts as a lecturer.

Featured guests:

In this episode, we are joined by Albert Lichtblau, former Deputy Director of the Center of Jewish Culture History and the History Department, at the University of Salzburg in Austria.

Albert will tell us more about Norbert’s story, and will discuss the difference in perspective that can be found in the testimonies of Holocaust survivors. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podcast Addict, Podcast Index or here:

“The Benevolent Dictator” and Albert Lichtblau: The Later Life of Norbert Abeles

As Albert Lichtblau recounts in this episode of our podcast, his first encounter with Norbert Abeles and the story of his life came quite by chance. Working on a project for the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, Lichtblau posted a call in 1997 for any unpublished biographical memoirs belonging to Austrian Holocaust Survivors who had emigrated.

It was in this way that Albert first encountered Norbert’s story, and the letter sparked a correspondence that first brought them together in 1998, when Albert visited Vienna to record Norbert’s testimony for the Shoah Foundation. Then, in 2012, Albert visited Norbert in Malawi and produced his documentary about Norbert’s live there.

The title of Lichtblau’s documentary comes from a quote of Abeles, whose later life in Malawi forms the centre of the film Lichtblau, working together with co-directors, and former students, Martin Hasenöhrl and Bernhard Braunstein, made about him. The quote is striking, not least because it is from a person whose own life was shaped by the escape from dictatorship. In the podcast, Lichtblau discusses the challenges of making the film with Abeles and navigating working with someone whose political and life views differ so greatly from his own. Norbert Abeles passed away on 27th November 2019.

Kindertransport

The “Kindertransport” was a rescue mission of more than 10,000 vulnerable and persecuted children from Nazi-occupied countries including Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria and Poland. The operation was established in the aftermath of the devastation of “Kristallnacht”, and the first such transport was overseen by Truus Wijsmuller and left Vienna in 1938 bound for Harwich. The rescued children were taken to the United Kingdom over the course of 1938 and 1939 in the lead up to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Situation in Austria WW2

Austria was occupied by the German Reich in March 1938 and annexed after a plebiscite. Many Austrians welcomed this “Anschluss”, after which they were treated equally as Germans – a separate Austrian identity was denied by the Nazis. Austria was integrated into the general administration of the German Reich and subdivided into administrative divisions called “Reichsgau” in 1939. In 1945, the Red Army took Vienna and eastern parts of the country, while the Western Allies occupied the western and southern sections.

In 1938, Austria had a total population of about 6,753,000 people. After the “Anschluss”, between 201,000 and 214,000 of them, including refugees from Germany, were persecuted as Jews under the Nuremberg Laws. The Austrian Nazi Party, which had been outlawed before the “Anschluss” in 1933, however, did not target only the Jews, but also other perceived “racial” enemies, political opponents of the Nazis, the disabled, and others. In the process, Austrians became involved in all types of Nazi crimes. In the first days and weeks of Nazi rule, Jews were subjected to brutal outbreaks of violence, including theft and murder. Subsequently, most Jews in the provinces were forced to move to Vienna. After the pogrom in November 1938, about 6,500 male Jews from Austria were imprisoned, and 4,000 among them were sent to the Dachau concentration camp. By late 1939, more than half of the German-Jewish refugees had resorted to emigration to escape from Nazi anti-Jewish measures in Austria. During the war, the remaining Jews in Austria were subjected to ever increasing isolation by new regulations, including forced transferal to smaller quarters and the introduction of the obligatory Jewish Star in September 1941. Austrian Jews were subsequently deported to Minsk, to camps and ghettos in Poland and to the Theresienstadt ghetto in Bohemia. Most of the deportees who initially survived were subsequently deported to extermination camps. Overall, around 66,000 Austrian Jews perished in the Holocaust.

Emigration of Jewish survivors

After the 1938 occupation of Austria, many thousands were forced to leave, fleeing persecution. As a result of tightening restrictions on leaving the country and the complications of obtaining visas for other Western European states, some Austrians also fled to Asia and Africa as a last resort.

Exact emigration figures for those who fled Austria to the East are little known, and the collection of essays in Going East – Going South Austrian exile in Asia and Africa, edited by Margit Franz, Heimo Halbrainer, makes an effort to re-trace these “lost histories” over the period 1938 – 1945. Albert Lichtblau’s essay in the collection details his study of Norbert Abeles’s own emigration in an attempt to shed more light on the experience of Austrian emigration to Africa.

Albert Lichtblau

Albert Lichtblau received his PhD in history and political science at the University of Vienna. He is a professor of modern and contemporary history and was vice chair and chair of the Center for Jewish Cultural History, as well as vice chair and chair of the Department of History at the University of Salzburg (Austria). His areas of scholarly expertise include qualitative methods, Jewish history, genocide, memory, migration studies, forms of representing history, oral history, and audiovisual history.

As well as “The Benevolent Dictator”, Lichtblau has also worked on several other documentary projects including “Erinnerungsbilanz Mauthausen” (2005) and “Wer ist Michael Gielen?” (2002).

Learn More

- Austria on the EHRI Portal

- Watch The Benevolent Dictator Documentary

- Maly Trostinec Camp on The Jewish Virtual Library

- Whittingehame Farm School

- Albert Lichtblau

- Leo Baeck Collection on EHRI Portal

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- Albert Lichtblau

- Martin Hasenöhrl and Bernhard Braunstein, co-directors of “The Benevolent Dictator”, for use of audio from the documentary.

- Our first EHRI intern Anthonia Prins for helping develop this remarkable story into a script

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks – Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14