Podcast Episode | Uncovering Hidden (Hi)stories

Release date: 12 December 2024 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead: Traces of the Holocaust

The final episode of the third series of the EHRI podcast takes a step back to look at micro-archives in a more general sense. In keeping with our theme, however, we also focus on an object that teaches us more about the Holocaust. An object that represents both the richness of sources that can be found in micro-archives and the challenges that those working with them face.

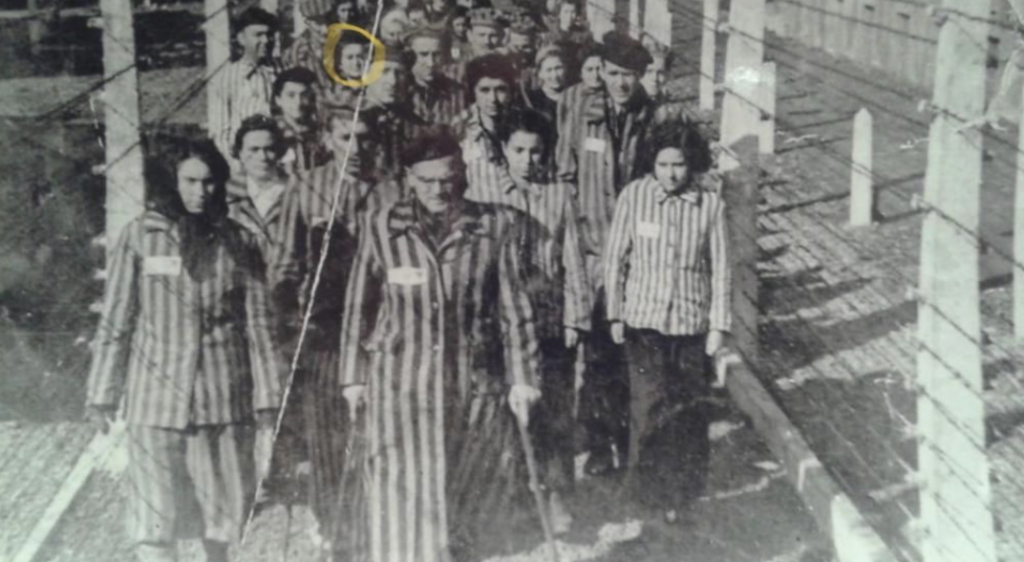

Our object of focus is the black and white photograph you can see below, depicting a group of prisoners dressed in the distinctive striped uniforms of Nazi concentration camps and walking along a corridor of barbed wire fencing. In the photograph, there is a woman in the fourth row from the front, circled in yellow. The woman’s name is Suzana Schossberger (Šosberger), and the photograph was taken by a Soviet military officer when Auschwitz was liberated in January 1945. Her son Mirko Stefanović remembers that his mother kept the photograph on a bookshelf in the living room, unframed and turned around. Mirko recalls how he never spoke to his mother about her imprisonment in Auschwitz even though she never tried to hide her experience and wore her tattooed prisoner number visibly.

The photograph came to the attention of Dr. Dora Komnenović, our guest for this episode, following a call launched by the Jewish Community of Novi Sad in preparation for the workshop “Archival Basics: A Hands-On Workshop for Micro-Archives”. This workshop was one of the several EHRI workshops for micro-archives organized by the German Federal Archives and other EHRI partners. Mirko answered the call almost immediately to contribute his mother’s remarkable photograph. He did this, as he explains in the testimony we hear in the episode, because of the responsibility he feels as part of the generation of survivors’ children to help preserve the memory of the Holocaust for the future. The photograph is important not only because of its subject matter, but because it represents the challenging first step towards building relationships with non-traditional archives. In the further exchanges Dora had with Mirko, she also found out about an oral testimony that Mirko’s mother gave to Yad Vashem in the 1990s. Mirko explained that he only listened to his mother’s testimony after her death and that he was not comfortable sharing it. This highlights the complex and emotionally charged nature of collecting such archival material from individuals and the relatives of survivors.

Suzana Schossberger was born and lived in Novi Sad, Serbia. She was the co-owner of a knitwear factory when, in April 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz along with her infant son, Andrija Schossberger and her father, Mirko Erdeš. Andrija and Mirko were sent directly to the gas chambers upon arrival and were murdered. Her husband, Tibor Schossberger, died of typhus as a prisoner of war.

Suzanna was selected by Mengele as a subject for experimentation. She was kept for some months in the hospital and subjected to unimaginable horrors before she could escape to the wider barracks where she managed to remain until the camp was liberated by Soviet soldiers in January 1945.

Featured guests:

Dr. Dora Komnenovic is a research associate at the Leibniz Centre for Contemporary History in Potsdam and an employee of the Federal Archives/Stasi Records Archive in Berlin. Podcast host is Katharina Freise.

Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podcast Addict or here:

More on this episode:

Suzana Schossberger’s life after liberation

After Auschwitz was liberated by Soviet soldiers, Suzana was identified as an important witness to be present at the Nuremberg trials, however, as Mirko recounts, a French Red Cross medic told authorities that Suzana should not be sent to the trial as it was unlikely that she would survive for more than six months. Despite this prognosis, Suzana went on to live a long life. She returned to Novi Sad and married Borislav Stefanovic, with whom she had two sons, Mirko and Vasilije. She repeatedly commented that she would have outlived the French medic. Mirko recalls that his mother never spoke to her children about her experiences in Auschwitz, but wore her prisoner number for all to see, which was A8806. Suzana died in 1996 at the age of 77.

More information on mirco-archives

In the podcast, Dr. Dora Komnenović refers to the EHRI description of a micro-archive, an association, memorial or grass-roots initiative that is not run by local authorities and does not receive state support nor any form of support from public means. Mirco-archives are particularly important for Holocaust research because Holocaust material is by nature incredibly fragmented; after the Second World War, important documents, objects and artefacts were scattered across Europe and beyond. Gathering together all of these pieces in a standardised, findable way is a core mission of EHRI and why micro-archival holdings are so important.

Despite their importance, these archives face many challenges. In particular, they often lack the contacts or resources to make their archives known. Language, too, can be an issue as translation is often required to make material sharable, and a lack of knowledge about correct preservation can often mean many key items and documents suffer over time. The most important thing for an archive or archival holding is to be findable, and this is something that EHRI strives to help with. EHRI has connections to researchers and larger archives that can help bring these smaller holdings into general knowledge. As Dora explains in the podcast episode, however, trust is a key factor in this endeavour – building relationships of trust with holders of micro-archives takes time but is of key importance.

Novi Sad workshop

Twelve participants from Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia gathered in Novi Sad, Serbia, to learn about the proper handling and storing of paper files, digitisation, archival description, user access and public relations. The program was complemented by talks on the history of the Jewish Community of Novi Sad, the EHRI project, Jewish heritage in the region of Vojvodina, and local initiatives in the field of Holocaust education.

Participants highly appreciated the hands-on part of the workshop that featured documents and photographs from the archive of the Jewish Community. By engaging with the documents, they had the opportunity to test their newly acquired knowledge and reflect upon the challenges an archivist faces when cataloguing documents. At the same time, they supported the archive of the Jewish Community with the organisation of some of its materials.

Besides transferring know-how, the goal of this workshop was to bring EHRI and the EHRI Portal closer to micro-archival communities in Southeastern Europe. The seminar was in fact preceded by an exploratory journey aimed at strengthening cooperation with micro-archival institutions in the region and creating sustainable networks, which shall accompany EHRI as it becomes an European Holocaust Research Consortium (ERIC).

Testimonies from the workshop

The workshop was co-hosted by the Novi Sad Jewish Community and organised by EHRI colleagues from the German Federal Archives. The ex-president of the Jewish Community, Mirko Štark, talks about the importance of the workshop to their archives that hold many precious documents dating from the 19thcentury up until now and are still awaiting research. According to Mirko Štark, they have gained significant knowledge from the workshop that will help them research and categorise these materials professionally and therefore make them accessible for further scientific research. For him, this is a big step for the small Jewish community of Novi Sad that is often approached by institutions, scientists, musicologist, and historians about material from the archive, which was so far not accessible. As Mirko Štark says, the small archive has now gained the necessary skills to make their holdings accessible to everyone interested, thereby offering a better service as a Jewish community. Mirko and the Jewish Community are grateful to Dr Dora Komnenović, Dr Angela Abmeier and Dr Nicolai M. Zimmermann for everything they have done to make this project a reality. You can listen to Mirko Štark’s account of the significance of the workshop here:

The workshop in Novi Sad was also attended by Biljana Albahari, a librarian at the National Library in Serbia who works on researching, locating, collecting, digitising and presenting books, printed materials, and documents related to Jewish heritage in Serbia and former Yugoslavia. Biljana provided several testimonies on her participation, some of which are part of the podcast episode Uncovering Hidden (Hi)stories. She applied for the workshop to learn more about EHRI’s mission and the German Federal Archives, one of the key archives of Nazi and Holocaust research, and to connect with other institutions active in Holocaust research and documentation in Serbia. She experienced the networking opportunity as more productive than official contacts, meeting colleagues from Serbia and learning from German experts in both formal and informal parts of the workshop. Although Biljana found the workshop overall very useful, she felt that an inclusion of local archives, e.g., the archive of Vojvodina that has already added data about their seven collections to the EHRI Portal, could have helped participants learn even more from practical experience.

During the informal parts of the workshop, Biljana spoke to Dora Komnenović about developing an episode for the EHRI podcast on the discovery of book donations to the National Library of Serbia by Samuilo Demajo, a well-known Belgrade lawyer who was killed in the Holocaust. The discovery of this donation by Andreas Roth, interviewed for the podcast episode The Stamp of Samuilo Demajo, motivated Biljana to do further research into this significant aspect of the history of the National Library of Serbia.

Finally, Biljana emphasised the need for further identification and integration of collections from Serbia into the EHRI Portal. Although 42 institutions in Serbia are listed as holding archival material of relevance to the Holocaust, only 8 have so far submitted their collections. Biljana further stressed that the National Library of Serbia holds various publications relating to the suffering and destruction of Jews and their property during the Holocaust in Serbia, such as posters, war declaration or rules, letters, photographs etc., that are currently not described or categorized. Her aim is to collect as many relevant documents of the National Library of Serbia as possible and to eventually integrate them into the EHRI Portal. As Biljana says, this would provide new insights into the Holocaust period in Serbia and former Yugoslavia. You can listen to Biljana’s account of the significance of the workshop here:

Importance of network created by EHRI

EHRI has made significant progress in identifying collection-holding institutions across Europe and beyond that hold Holocaust-related archival collections and has integrated information about their holdings into the EHRI Portal. While the Portal’s trans-national coverage of such institutions is already very comprehensible, gaps remain. Much valuable archival material is held by small, purely local players (small institutions, local grass-root initiatives, private individuals). Connecting the materials that these micro-archival communities hold is challenging as EHRI’s existing data identification and integration methods are calibrated mainly for use by larger institutions.

Serbia during WW2 in EHRI Portal

An internationally recognised independent state since 1878, Serbia joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918, which then became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. In April 1941, when Germany’s twelve-day campaign against Yugoslavia led to its partition between the Axis powers and their allies, the Yugoslav government was evacuated to London. Following capitulation, most of Serbia’s present-day territory was administered by the German military under the “Militärbefehlshaber Serbien” in Belgrade. The rest of the territory was annexed by neighbouring countries: northern Bačka by Hungary; some south-east areas by Bulgaria, the south-west areas by Italian-controlled Albania; and the north-west Syrmia region by the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska), which had been formed on 10 April 1941. The German occupiers were driven out of the Yugoslav capital Belgrade by the Red Army and local Communist partisan units in October 1944. Serbia then became one of six republics within the post-war Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia dissolved during the 1990s, Serbia became an independent state again.

In 1941, about 33,500 Jews lived in Serbia, among them some 16,000 lived in the German occupied areas of Serbia, out of a population of about 3,810,000. Soon, the new authorities issued anti-Jewish laws. Those considered Jews were forced to wear the Jewish badge, expelled from certain professions and restricted to living in certain areas. By the summer of 1941, all Jewish men between the ages of 16 and 60 were rounded up for forced labour. Jews also fell victim to German reprisals against the local resistance movement. Notably, the German military authorities threatened to retaliate by executing 50 Serbian hostages for every German injured and 100 for every German soldier killed; the Germans met their quota by executing Jews, hoping to avoid antagonising the gentile local population any further. By early autumn 1941, most of the Jewish men of Serbia had been imprisoned in local concentration camps, and mass executions began. By December, the majority of Jewish men, about 5,000 people, had been killed. Exceptions were made for those who were needed for forced labour. At the same time, about 8,000 Jewish women, children and elderly people were sent to a fairground which had been turned into an internment camp at Sajmište near Belgrade. From March to May 1942, more than 6,000 inmates were killed in gas vans, while another 1,200 died of exposure or starvation. By the summer of 1942, only a very few Jews were left in Serbia, surviving either by hiding or by joining the Partisans. In total, about 14,500 Jews were murdered in the German-controlled part of Serbia during the war.

In the Bulgarian-occupied zone of Serbia—Macedonia and southeast Serbia—Jews were arrested in 1943 and deported to the Treblinka death camp. In the Hungarian-occupied part of Serbia, Jews were among the victims of the Hungarian killings at Novi Sad in January 1942. In the Albanian-occupied area of Serbia, the Germans, supported by an Albanian SS-Division, arrested Jews from Kosovo and Jewish refugees from other parts of Yugoslavia. They were sent to the Sajmište camp and one month later to Bergen-Belsen. In the entirety of present-day Serbia, some 27,000 Jews out of about 33,500 (over 80%) perished.

Dora Komnenović

Dora Komnenović obtained her PhD in Social and Cultural Studies at Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany. She holds a BA in International Relations and Diplomacy (Trieste University, 2010) and an MA in Interdisciplinary Research and Studies on Eastern Europe (Bologna University, 2012). Her research interests revolve around the practice and theory of public history, European politics and memory. One of Dora’s latest research projects dealt with the discarding of books in (post-)Yugoslavia, a topic on which she wrote several book chapters, articles and most recently a monograph titled “Reading between the Lines: Reflections on Discarding and Sociopolitical Transformations in (Post-)Yugoslavia” (ibidem, 2022).

From March 2023 to August 2024, she worked for EHRI partner Das Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives) on the EHRI project. Among other things, she organised a workshop for micro-archives, especially those in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, in Novi Sad. She is now a research associate at the Leibniz Centre for Contemporary History Potsdam and an employee of the Federal Archives/Stasi Records Archive, Berlin. In January 2025, Dora will take on a new position at the University of Luxembourg.

Learn More

- Jewish Community of Novi Sad

- The EHRI Podcast Episode about Samuilo Demajo

- Biljana Albahari’s lecture on the Demajo collection of books

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- Dora Komnenović

- Mirko Stefanović for the use of the photograph and his testimony

- Biljana Albahari and Mirko Štark for their testimonies

- Our first EHRI intern Anthonia Prins for helping develop this remarkable story into a script

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks – Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14