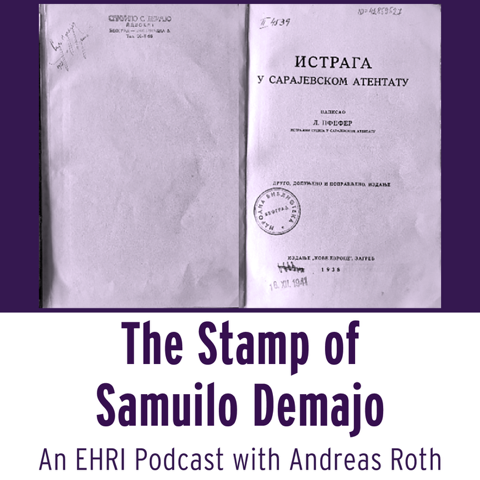

Podcast Episode | The Stamp of Samuilo Demajo

Release date: 17-10-2024 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

The Stamp of Samuilo Demajo

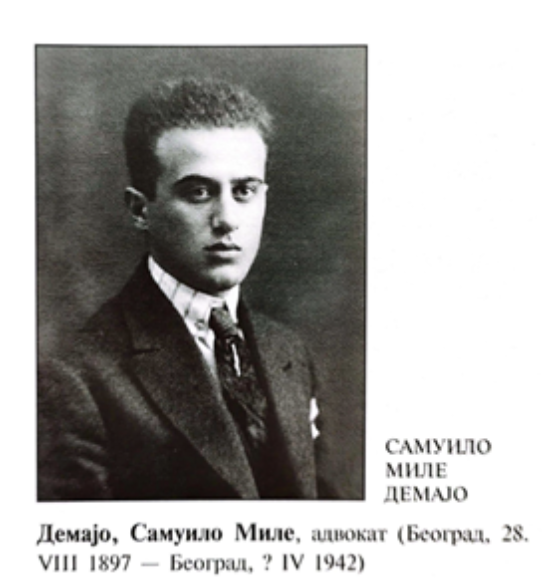

In this episode, we focus on a stamp, printed on the inside jacket of a book donated to the National Library of Serbia in 1941. The stamp is remarkable not least because it belonged to a prominent Belgrade lawyer named Samuilo Demajo, whose family was murdered in May 1942 in a Dušegupka, a truck re-equipped as a mobile gas van. Though Demajo’s life was abruptly ended, his legacy lives on in this and the approximately 200 other books that he donated in an effort to rebuild the public library.

Demajo was born in 1898 into a prominent Belgrade Jewish family, doing his Military Service after the First World War before studying law and becoming a lawyer. As an active member of his community, he was involved in social initiatives and local politics as well as a member of the Belgrade City Assembly. After the National Library of Serbia was bombed by Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe and its precious collections destroyed by fire between 6 – 9 April 1941, a public call was put out for donations to rebuild the library’s collection. 6th April 1941 also marked the beginning of World War II in former Yugoslavia and the control of Belgrade as well as other parts of German-occupied Serbia by the “Militärbefehlshaber Serbien” (territory of the military commander in Serbia). Persecution of Serbian Jews began immediately, with strict laws and restrictions against their movement, rights, employment and citizenship. Nevertheless, in May 1941, Samuilo Demajo responded to the public call of the library and made the generous offer of a donation of 133 “works from all fields of science and literature”. Due to the restrictive laws against Jews, it was prohibited for Demajo’s donation to be accepted, but the then-director of the National Library corresponded with the German authorities and an exception was made. Demajo later added around 60 bound volumes of newspapers and magazines, stenographic notes from the National Assembly, and collections of laws and decrees.

The stamp was found by Andreas Roth, who was doing research in the National Library of Serbia in 2014. The discovery led to Andreas conducting a research project with a teacher colleague and a handful of history students, to try to uncover the story behind the stamp and retrace the lost history of the Demajo family. Through their research, the group were able to identify the history of the family and uncover details about their lives in Serbia before the war, after the occupation and ultimately leading to their tragic murders in May 1942.

in front of the German pavilion at

the Belgrade fair

Featured guests:

In this episode, we are joined by Andreas Roth, historian and secondary school history teacher who taught at the German School in Belgrade between 2012 and 2020.

Andreas will tell us more about the stamp he discovered and the journey that it took him, his former colleague and their students to uncovering the story of the Demajo family. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts or here:

Letter of Donation from Samuilo Demajo to the Serbian National Library (translated from Serbian)

“To the National Library

It is my honour to hand you 133 works from all fields of science and literature for the National Library. I am giving you the books as my least contribution with the desire that our institution, where we all have spent so many precious hours, is renewed and once again serves its lofty goal.

With respect,

S. Demajo”

Letter of Approval from the Minister of Education (translated from Serbian)

“Ministry of Education

General Department

No. 2323

February 18, 1942

Belgrade

To the National Library, Belgrade

Regarding the books donated to the National Library in Belgrade by the late Solomon M. Demajo, a former merchant from Belgrade, the late Šemaja M. Demajo, a former lawyer from Belgrade, and Samuilo Demajo, a lawyer from Belgrade, the Presidency of the Council of Ministers forwarded to the Ministry of Education the answer of the Administrative Staff of the Plenipotentiary General in Serbia no. 741/42/V, which reads as follows:

“Concerning your letter, I declare that I am ready to exempt the case reported to me from the application of the Decree on the Accommodation of Jews of December 22, 1941. However, I expressly note that this decision applies only to this individual case, while the application on similar cases is prohibited (not allowed), if there are such cases, my consent must be obtained again”.

The Library is informed of the above for their knowledge and proper procedure.

By order of the Minister of Education

Head of the General Department”

Serbia in the Second WW on the EHRI Portal

An internationally recognised independent state since 1878, Serbia joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918, which then became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. In April 1941, when Germany’s twelve-day campaign against Yugoslavia led to its partition between the Axis powers and their allies, the Yugoslav government was evacuated to London. Following the capitulation, most of Serbia’s present-day territory was administered by the German military under the “Militärbefehlshaber Serbien” in Belgrade. The rest of the territory was annexed by neighbouring countries: northern Bačka by Hungary; some south-east areas by Bulgaria, the south-west areas by Italian-controlled Albania; and the north-west Syrmia region by the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska), which had been formed on 10 April 1941. The German occupiers were driven out of the Yugoslav capital Belgrade by the Red Army and local Communist partisan units in October 1944. Serbia then became one of six republics within the post-war Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia dissolved during the 1990s, Serbia became an independent state again.

In 1941, about 33,500 Jews lived in Serbia, among them some 16,000 lived in the German occupied areas of Serbia, out of a population of about 3,810,000. Soon, the new authorities issued anti-Jewish laws. Those considered Jews were forced to wear the Jewish badge, expelled from certain professions and restricted to living in certain areas. By the summer of 1941, all Jewish men between the ages of 16 and 60 were rounded up for forced labour. Jews also fell victim to German reprisals against the local resistance movement. Notably, the German military authorities threatened to retaliate by executing 50 Serbian hostages for every German injured and 100 for every German soldier killed; the Germans met their quota by executing Jews, hoping to avoid antagonising the gentile local population any further. By early autumn 1941, most of the Jewish men of Serbia had been imprisoned in local concentration camps, and mass executions began. By December, the majority of Jewish men, about 5,000 people, had been killed. Exceptions were made for those who were needed for forced labour. At the same time, about 8,000 Jewish women, children and elderly people were sent to a fairground which had been turned into an internment camp at Sajmište in Belgrade. From March to May 1942, more than 6,000 inmates were killed in gas vans, while another 1,200 died of exposure or starvation. By the summer of 1942, only a very few Jews were left in Serbia, surviving either by hiding or by joining the Partisans. In total, about 14,500 Jews were murdered in the German-controlled part of Serbia during the war.

In the Bulgarian-occupied zone of Serbia—Macedonia and southeast Serbia—Jews were arrested in 1943 and deported to the Treblinka death camp. In the Hungarian-occupied part of Serbia, Jews were among the victims of the Hungarian killings at Novi Sad in January 1942. In the Albanian-occupied area of Serbia, the Germans, supported by an Albanian SS-Division, arrested Jews from Kosovo and Jewish refugees from other parts of Yugoslavia. They were sent to the Sajmište camp and one month later to Bergen-Belsen. In the entirety of present-day Serbia, some 27,000 Jews out of about 33,500 (over 80%) perished.

Biljana Albahari

Biljana Albahari is a librarian advisor in the National Library of Serbia and has conducted further research on the Demajo collection of books. Through the correspondence of the prewar director of the National Library with the occupation authorities, Albahari has been able to follow how the books were kept in the library. From the address given on Demajo’s donation letter, his office at Jakšićeva 5, Albahari was able to ascertain that the books were likely delivered to the library by volunteers or library staff themselves because by the date of the letter, May 26 1941, the movements of Jews in Belgrade were already heavily restricted.

Through following the library’s ‘dramatic’ history and the several moves its collection endured during the war period, Albahari has been able to begin to try to answer the question of if Demajo’s donated books have survived such turbulent storage. Albahari states that “The only way to find gifted books and periodicals bearing the Demajo family stamps is to check each copy on his list. After such a check, each found book from Demajo’s legacy can be given an appropriate bibliographic note and eventually be separated as a Demajo collection.”

Albahari’s research into the Demajo family also deals with the photograph’s origin from 1940, when Samuilo Demajo and his family were photographed in front of the German Pavilion at the Belgrade Fair. She talks about this during her presentation given as part of the “Zoom Shabbat”, organized by the Jewish Community of Belgrade and the technical support of Raka–Levi, on December 22, 2023 (that is available here in Serbian on the Jewish Digital Library). This photograph is in the public domain and can be freely downloaded from the Internet. It is well-known to most Holocaust researchers, and often used by educators and historians. However, formal bibliographic data about the source or collection in which the photograph is located does not exist; the owner of the collection and its physical whereabouts remain unknown. The photograph depicts not only the active nature of the Demajo family in social and cultural activity in Belgrade at the time, but contains striking foreshadowings of the future. The Belgrade fairground site with the German pavilion, seen looming behind the family in 1941, would the following year be transformed into a concentration camp where they would be imprisoned and tragically murdered.

Andreas Roth on the benefits of using micro archives for teaching history

Andreas Roth is a German secondary school history teacher and taught history at the German School of Belgrade between 2012 and 2020. Roth found the stamp inside a book by Leo Pfeffer in the National Library of Serbia. Demajo’s stamp inside the cover of the book contained not only his name and profession, a lawyer, but also the address and phone number of his office, providing Roth with enough information to follow the interest that his discovery sparked. Roth argues for the study of history on an individual level and emphasises the importance of doing this kind of micro-level research to combat the kind of generalized, group thinking that characterised the Nazi’s persecution of people across Europe. Using micro-archives, or focuses on primary sources for historical education, he explains in this episode, has a fundamental impact on the way students perceive people from the past. Through researching the Demajo family and tracing their individual lives and history, he said students he worked with developed profound empathy for the fate of the family and changed the way that they thought about and dealt with the study of people from the past.

Learn More

- Serbia on the EHRI Portal

- Biljana Albahari’s lecture on the Demajo collection of books

- Historical Archive of Novi Sad

- Archives of Vojvodina

- Jewish Digital Library

- Jewish Historial Museum

- Historial Archive of Belgrade

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- Andreas Roth

- Andreas Roth and Biljana Albahari

- Raka Levi for kindly reading extracts of the correspondence between the National Library of Belgrade and the Ministry of Education and the head of the General Department and Anđela Čagalj for talking about her experience as a student of Andreas Roth

- Our first EHRI intern Anthonia Prins for helping develop this remarkable story into a script

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks – Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14