Podcast Episode | Gita’s Notes for Survival

Release date: 14 December 2023 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

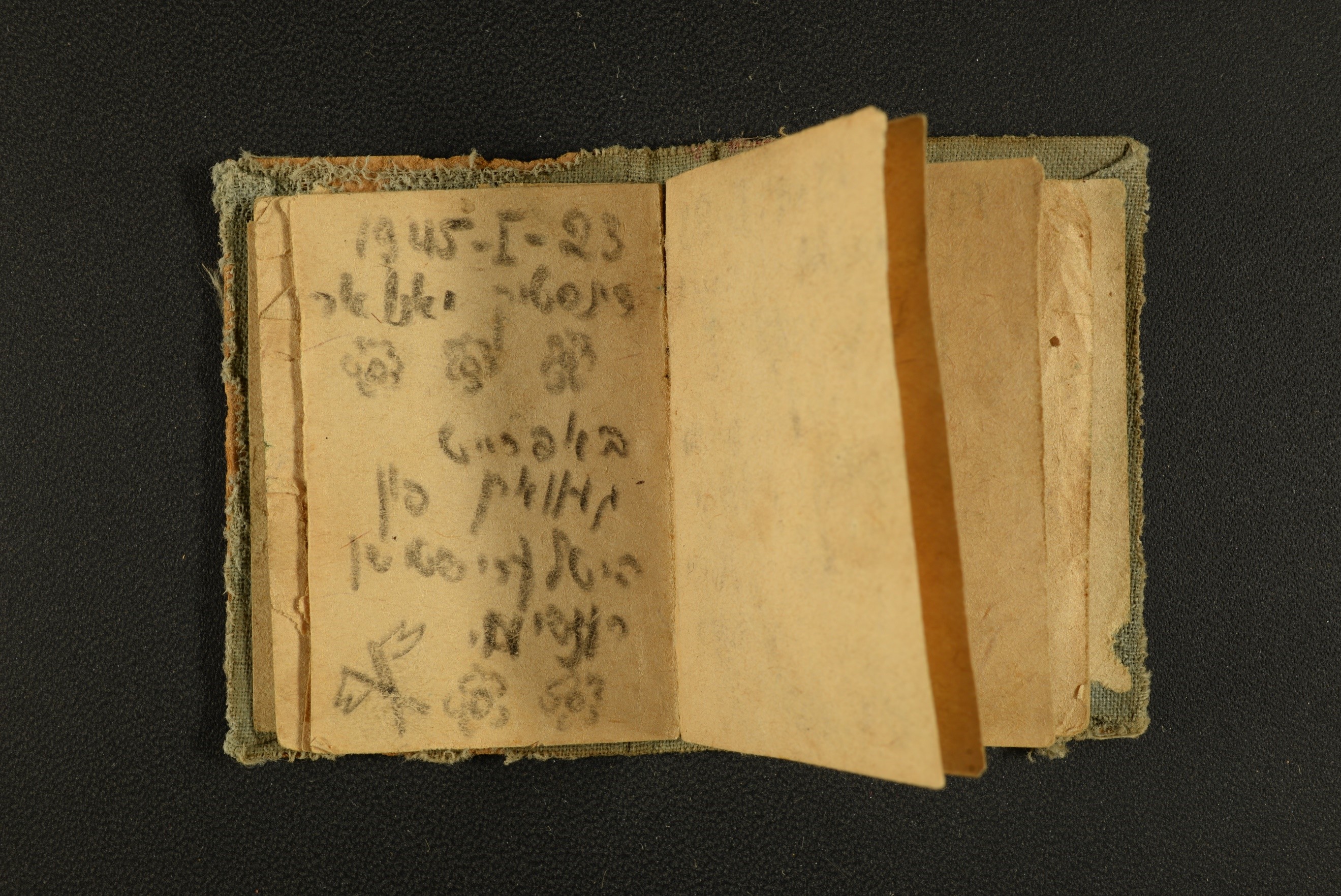

In this podcast episode, released during Hanukka 2023, we talk with Ofer Lifshitz about a tiny memory booklet, as small as a young girl’s fist, that belonged to a teenage girl named Gita Rubanenko.

Gita was born in 1929 and lived with her parents and sister in a town called Kovno in Lithuania. Kovno, also known as Kaunas, was before the war the capital and largest city of Lithuania. In 1939, Kovno had a vibrant Jewish community with approximately 32,000 people, about one-fourth of the city’s population.

In June 1940, Kovno’s everyday life was horribly disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania. When Nazi Germany took over a year later, and Gita was twelve years old, life for the Jewish community became impossible. Many were murdered by the Einsatzgruppen. During the summer of 1941, German occupation officials concentrated the remaining Jews in Kovno ghetto, an area of small, primitive houses and no running water. Kovno ghetto was officially sealed on August 15, 1941. Gita and her family were trapped inside.

Life in the ghetto was harsh and during several ‘Aktions’ thousands were again murdered. Still, those surviving, like Gita, maintained a form of daily life and human dignity. In July 1944, the ghetto was evacuated and most of the remaining Jews were deported. Gita’s family was sent to the Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland).

Conditions in the camp were brutal. Gita’s parents and sister were murdered. Gita survived. And with her her ‘Knizhechka’. In this small booklet, Gita recorded what she witnessed throughout the war. Not with elaborate words, but more like dry facts.

After the war, Gita returned to Kovno and later emigrated to Israel, where she married and had a daughter. She kept the Knizhechka with her until her death in 2020. Her daughter, Hasia Mandel, gave it to Yad Vashem for safekeeping after her mother had passed away.

Uniquely, Hasia and her two children, Elhanan and Sharon (Gita’s grandchildren) can be heard in this podcast episode, reciting from the Knizhechka.

Featured guests:

Ofer Lifshitz was until recently content producer and editor for the Gathering the Fragments Project of Yad Vashem, the World Holcoaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Ofer now works at Tel Aviv University.

Podcast host is Katharina Freise.

Ofer will tell the story of Gita Rubanenko and her very special notebook. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or here:

When we came to Stutthof, we were sent to the bathrooms – no, it was a bathing house.

When we came to Stutthof, we were sent to the bathrooms – no, it was a bathing house.

At the bathing house, they took everything away from us, even the soap, even the jam can.

Everything.

Only this small booklet (knizhichka) – I was able to hold on to.

I held it in my hand. Just like that

Can you see? This is how I held it.

This is all I have left.

Gita Rubanenko (nee Feinberg), Yad Vashem’s Testimony Collection, 1988

How does a teenage girl react to the constant and ongoing exposure to death in the ghetto that gradually separates her from her family and community, until she is left all on her own?

Gita was twelve years old when her home town of Kovno, Lithuania, was taken over by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Barbarossa (June, 1941). The mass murder of the Jews of Kovno in fortresses overlooking the city started within weeks of the German occupation, as well as steps towards ghettoization and the removal of Jews from society.

Gita’s instinctive response was to come up with a memory book – or ‘Knizhechka’ (booklet), as she would later refer to it in her testimony for Yad Vashem in 1988. Written in Yiddish, almost in shorthand, in a fist-sized pocket notebook, Gita’s memory book represents the framework of her life during the War – intertwined with the story of the Kovno Ghetto, where she was living until the Ghetto’s evacuation in the summer of 1944. Gita’s memory booklet is arranged in diary form: dated entries, dedicating but a mere sentence to each of the events that Gita had witnessed and recorded: the main Aktions in the Ghetto, the deaths of Gita’s loved ones, the evacuation of the Ghetto, Gita’s deportation to Stutthof and her liberation.

“The tragic death of my dearly beloved Father – ghetto evacuation” (10.7.1944)

“Torn apart from my dearly beloved Mother and Sister – Stutthof” (27.7.1944)

“Freed from the Hitlerite Regime” (23.1.1945)

In Gita’s memory book, the entry that dates back to March 27th, 1944, consists of five words: “The Kinderaktion in the Ghetto”.

Gita’s testimony from 1988 reveals the dramatic circumstances behind these five words: she and her younger sister Shayna were hidden by their parents in the family’s bathroom, the entrance to which was concealed by a bookcase. This is how the parents managed to save both their daughters – for the time being. They took in other children as well. About 200 children were hidden and saved in the ghetto altogether. Some 1,300 children were murdered in a hunt throughout the ghetto as part of what became known as the Kinderaktion. “No more children were seen in the ghetto,” recalled Gita. “Even those who remained alive, were hidden… so that no one could see them.”

Gita’s Knizhechka is a touching demonstration of individualized grassroot attempts to preserve memory and identity during the Holocaust, defying dehumanization and oblivion – using whatever resources and means that were at hand. On the one hand, Gita’s memory book is the improvised and spontaneous – yet consistent – choice of a girl to document what she saw. On the other hand, it is much reminiscent, and in the spirit of, the Jewish tradition of the Jahrzeit and the Yizkor, dating back to the Middle Ages: making use of prayer books to record the deaths of family members and mentioning their names during communal services as means of commemoration.

Gita’s Knizhechka is a touching demonstration of individualized grassroot attempts to preserve memory and identity during the Holocaust, defying dehumanization and oblivion – using whatever resources and means that were at hand. On the one hand, Gita’s memory book is the improvised and spontaneous – yet consistent – choice of a girl to document what she saw. On the other hand, it is much reminiscent, and in the spirit of, the Jewish tradition of the Jahrzeit and the Yizkor, dating back to the Middle Ages: making use of prayer books to record the deaths of family members and mentioning their names during communal services as means of commemoration.

Gita was able to hold on to her ‘Knizhechka’ as a prisoner in Stuttfhof and kept it with her all her life.

Kovno Ghetto

In July and August 1941, German occupation officials concentrated the then remaining Jews of Lithuania, some 35,000 people, in a ghetto that was sealed on August 15, 1941.

Kovno ghetto was established to provide forced labor for the German military. Jews were employed primarily as forced laborers at various sites outside the ghetto. The Jewish council also created workshops inside the ghetto for those women, children, and elderly who could not participate in the labor brigades. Eventually, these workshops employed almost 6,500 people. The council hoped the Germans would not kill Jews who were producing for and supporting the German war effort.

In its first few months of existence, the ghetto had two parts. These parts were called the “small” and “large” ghettos. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the size of the ghetto, forcing its Jews to relocate several times.

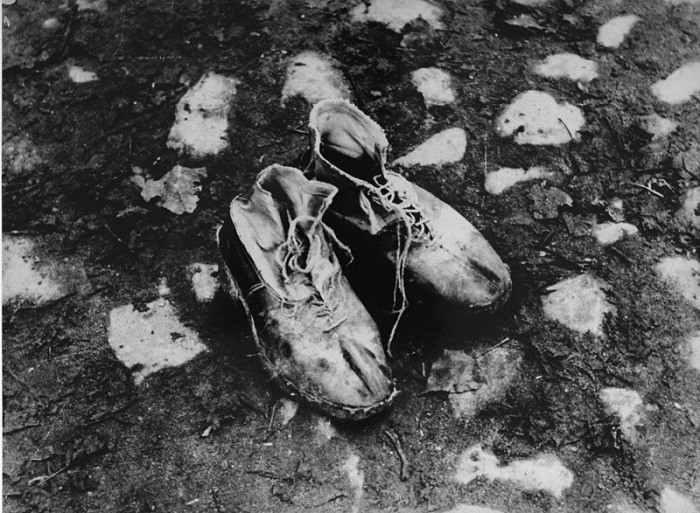

Photographer George Kadish captioned the photo “The body is gone.”

Kovno, Lithuania, circa 1943. US Holocaust Memorial Museum,

courtesy of George Kadish/Zvi Kadushin

On October 4, 1941, the Germans liquidated the small ghetto and killed almost all of its inhabitants at Fort IX, one of the forts around the city. Later that same month, the Germans staged what became known as the “Grosse Aktion“. Occupation officials selected close to 10,000 ghetto inhabitants they deemed “unfit” for forced labor, many children among them. On October 29, 1941, Einsatzgruppen units shot most of these individuals at Fort IX. The death toll on that one day was 9,200 Jews.

In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kauen concentration camp. The Jewish council’s role was drastically curtailed. The Nazis dispersed more than 3,500 Jews to subcamps where strict discipline governed all aspects of daily life. On October 26, 1943, the SS deported more than 2,700 people from the main camp. The SS sent those deemed fit to work to labor camps in Estonia, and deported children and the elderly to Auschwitz. Few survived.

On July 8, 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kovno, the Germans razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2,000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape.

The Soviet army liberated Kovno on August 1, 1944. Of Kovno’s few Jewish survivors, 500 had survived in forests or in bunkers.

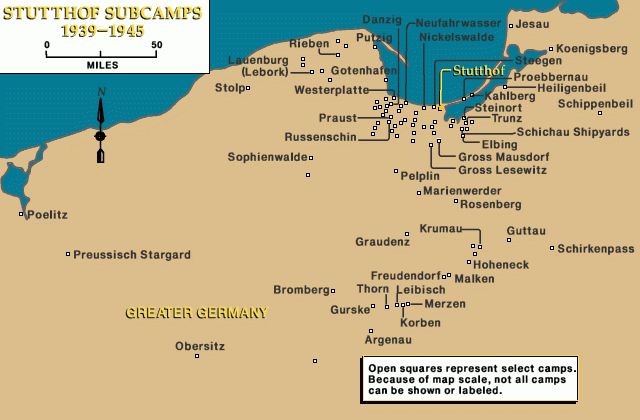

Stutthof Concentration Camp

In September 1939, the Germans established the Stutthof camp in a wooded area, east of Danzig (Gdansk). First a civilian internment camp, than a labor camp, in 1942 became a regular concentration camp. Tens of thousands of people, in the beginning mostly non-Jewish Poles, were deported to the Stutthof camp. The Germans used Stutthof prisoners as forced laborers. Eventually, the Stutthof camp system became a vast network of over a hundred forced-labor camps. Conditions in the camp were brutal and many prisoners died in typhus epidemics. Those too weak or sick to work were gassed in the camp’s small gas chamber. More than 60,000 people died in the camp.

With the Soviet Army approaching, the evacuation of prisoners from the Stutthof camp system began January 1945. When the final evacuation began, there were nearly 50,000 prisoners, by then the overwhelming majority of them Jews. About 5,000 prisoners from Stutthof subcamps were marched to the Baltic Sea coast, forced into the water, and machine gunned. The rest of the prisoners were marched in the direction of eastern Germany. They were cut off by advancing Soviet forces and the Germans forced the surviving prisoners back to Stutthof. Marching in severe winter conditions and treated brutally by SS guards, thousands died during the march.

Soviet forces liberated Stutthof on May 9, 1945, and liberated about 100 prisoners who had managed to hide during the final evacuation of the camp.

Gita was imprisoned in one of the major subcamps of Stutthof, Thorn (Torun). She was liberated there by the Red Army in January 1945: “Freed from the Hitlerite Regime” (23.1.1945)

Ofer Lifshitz and Yad Vashem

Ofer Lifshitz was academically trained in cultural research at Tel Aviv University and worked as content producer and editor for Yad Vashem’s Gathering the Fragments Project. As part of his work for the Yad Vashem Archives, Ofer has taken part in collecting, reviewing, and studying testimonies and collections of Holocaust-related materials. Ofer has participated in various social projects associated with communicating preserving Holocaust memory.

Ofer Lifshitz was academically trained in cultural research at Tel Aviv University and worked as content producer and editor for Yad Vashem’s Gathering the Fragments Project. As part of his work for the Yad Vashem Archives, Ofer has taken part in collecting, reviewing, and studying testimonies and collections of Holocaust-related materials. Ofer has participated in various social projects associated with communicating preserving Holocaust memory.

The Gathering the Fragments Project is a national campaign launched in Israel to rescue personal items from the Holocaust period that can still be found in many homes. This important campaign appeals to Holocaust survivors, family members and the general public to search their homes for items from the years before the war, during the Holocaust and the immediate post-war period and submit them to Yad Vashem for safekeeping. These items, such as photographs, letters, diaries, art works, tell important stories about what happened to the Jews before, during and after the Holocaust. Gita’s daughter, Hasia Mandel, gave her mother’s memory booklet to Yad Vashem after her mother’s death in 2020. Ofer is now based at Tel Aviv University.

Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, is Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. Yad Vashem’s vision, as stated on its website, is: “To lead the documentation, research, education and commemoration of the Holocaust, and to convey the chronicles of this singular Jewish and human event to every person in Israel, to the Jewish people, and to every significant and relevant audience worldwide.” Yad Vashem has been a partner of EHRI since the beginning in 2010.

Learn More

- Testimony of Gita Rubanenko, 1988, Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem, Gathering the Fragments

- Kovno Ghetto, from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Stutthof Concentration Camp, US Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Lithuania in the EHRI Portal

Credits:

Our thanks go to:

- Gita Rubanenko, who gave her testimony in 1988 to Yad Vashem and donated also her knizhichka after she died through her daugther Hasia Mandel

- Yad Vashem, in particular Ofer Lifshitz and his colleagues for their special help and inspiration. From Yad Vashem’s Archives Orit Noyman, who received the Knizhechka, Olga Litwak and Ilona Angert for their work on Gita’s testimony, and Hillel Solomon for bringing Gita’s story to our attention as well as Adir Barel from Yad Vashem’s Technical Department.

- Hasia Mandel and her grandchildren Elhanan and Sharon, who gave their voices to Gita’s testimony in English and read Gita’s notes in the knizhechka

- Images courtesy of Yad Vashem, except when mentioned otherwise.

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks – Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14