Education | The Remediation of the Holocaust Narratives in the History Classroom

Emma Abbate has a PhD from the Università Federico II di Napoli and is a CLIL teachers trainer at the Università L’Orientale di Napoli and a teacher at Liceo Scientifico Armando Diaz Caserta.

She participated in the EHRI workshop Challenges in Presenting Holocaust Resources in the Digital Age, that took place at Yad Vashem in November 2022, and has written a blogpost about her contribution that gives insight in modern Holocaust education.

In Holocaust education, the need for a student-centered approach and the increasingly active role of the learners acting more as co-creators of contents than simple interlocutors, call for a creative but ethically respectful remediation of primary sources employed in classrooms. This post describes some digital learning experiences aimed at renewing students’ agency in Shoah remembrance, it is the summary of my contribution to the EHRI workshop “Challenging in presenting Holocaust resources in the Digital Age” in Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, in November 2022.

Mapping Technology for a Geography of the Holocaust Literature

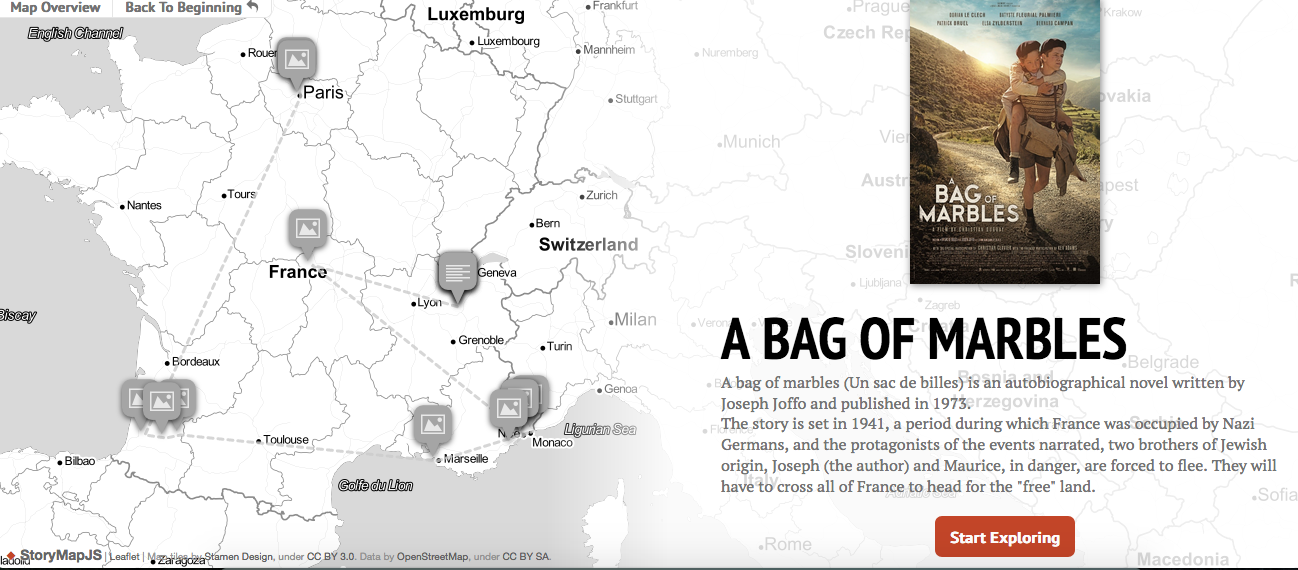

What is usually missing in addressing Shoah-related narratives in the classroom is the combination of historical sources with personal descriptions of the physical sites where persecution took place: to fill this gap, my students were assigned the task of reading the autobiographical novel “A bag of marbles” by Joseph Joffo[1], the Odyssey of two Jewish young brothers fleeing Nazi-occupied Paris to get to the south where France was free.

Because of its strong location narrative, this book was ideal to be translated visually with the support of mapping technology.

Pupils were asked to use StoryMapJS, a free and friendly author tool, to retell and trace the children’s forced journey inserting their memories into both temporal and spatial perspectives.

Spatializing the story of the survivors and acting as mapmakers, gives learners the opportunity to experience it closely illuminating the resilience and courage that each survival story tells.

Enriched with book quotes, pictures from the film adaptation, and video clips of the Joffo brothers’ interviews, the StoryMapsJS realized by students become interactive multimedia representations of the survivors’ testimonials: events recounted by the writer are embedded into a wider history of the Shoah and the Second World War in order to get a complete picture of the spaces and places where Holocaust was enacted and experienced.

The Holocaust in Metaverse

Especially after the pandemic, schools are increasingly embracing Virtual Reality (VR) experimentation to implement new learning spaces and more intensely engage learners.

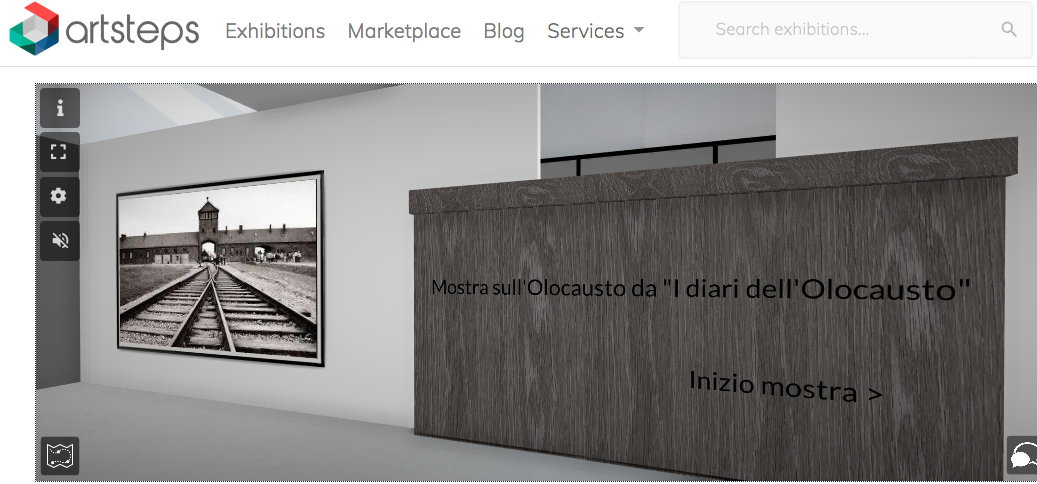

A good example of VR application in Holocaust teaching, is asking students to create a virtual exhibition on testimonies: this will give them the chance to conduct accurate and extensive research on primary sources, to connect truly with the available material, and to demonstrate their knowledge of events in an attractive way.

I asked pupils to analyze the “Young writers diaries of the Holocaust” collected by Alexandra Zapruder[2] in order to design a virtual exhibition of the lives of the young narrators.

To accomplish the given task, students used Artsteps: it is free- web based software that allows users to create virtual art/museum galleries within 3D spaces. Learners worked intensively on the sources to define how to insert them in the space of the virtual area: they placed walls, labels, and guide points across the online exhibition to share the children’s stories according to their own narratives, and carefully selected colors and textures to create an immersive, simulative and responsive storytelling experience for the visitors of the virtual tour.

The second VR project my classes worked on, was the virtual and historically accurate reconstruction of the Terezin Concentration Camp based on Petr Ginz’s journal’[3]s descriptions and developed with Mozilla Hubs, a free, virtual collaboration platform that allows to create 3D spaces and invite others to join using a URL.

Students presented this three- dimensional reconstruction within a three-wall-projection space: the school’s Immersive classroom. The immersive interactive presentation was made possible thanks to a deep analysis of the historical spatial structures and details of fences, buildings, and camp sections, in order to faithfully recreate them.

Students carefully processed Petr’s diary to replicate the digital space as accurately as possible, gathering references and investigating objects which were filling the camp: all the information and descriptions contained in the journal about the former camp were taken into account to reproduce the detailed 360° stereoscopic view. Designing and realizing the camp allowed them to fully acquire the journal’s content and to boost digital competence.

With the aid of a compatible VR set (Oculus Rift, Windows Mixed Reality, or HTC Vive) the students become also guides within the digital camp, thus increasing their presentation and communication skills in helping visitors experience the 3D space.

The Holocaust storytelling in an Instagram Age

New mediated practices of Holocaust remembrance reveal attempts to shift from text-based to image-centered content: it is the case of a controversial and debated project, Eva.Stories, which translated into a fictitious Instagram account the real-life story of Eva Heyman, a Jewish Hungarian girl murdered in Auschwitz.

The account is the digital adaptation of Eva’s diary[4], the events are, thus, displayed through the typical social media effects: videos, graphics, stickers, hashtags, selfies, internet slang, and emoji.

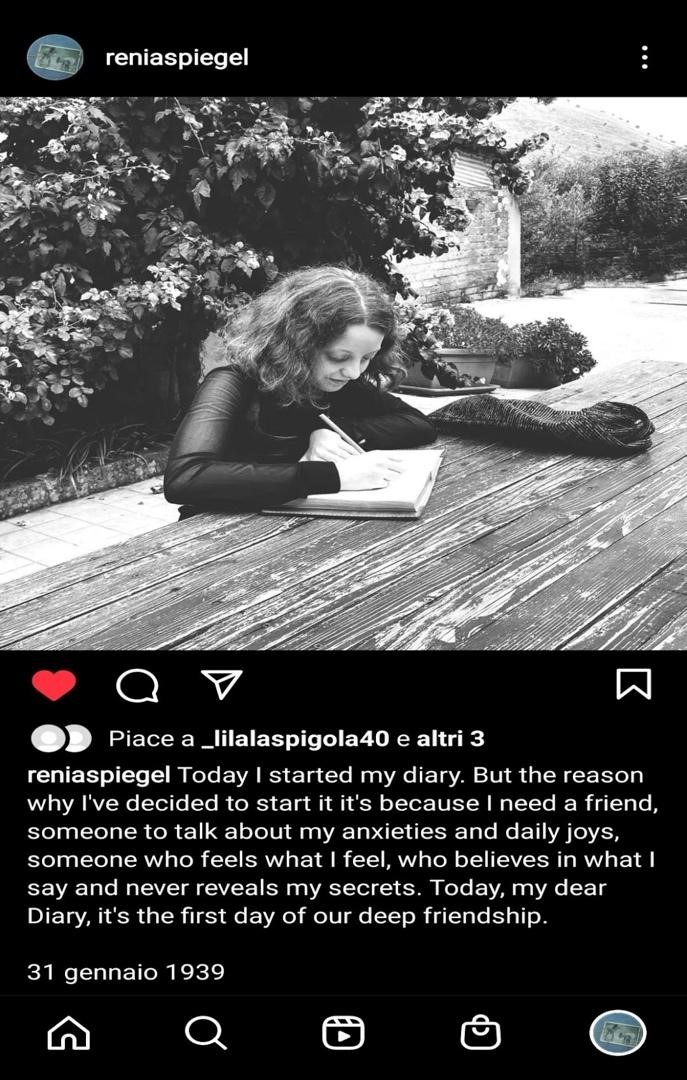

The idea to engage my students in a similar project stemmed from their positive reaction toward Eva.stories: the Instagram account had attracted their interest, and they were eager to go further in the narration of her life. Thus, I suggested they portray the life of Renia Spiegel through the design of her Instagram account. Reina was a Polish teenager who started to write her journal in 1939, it ends in July 1942, completed by Renia’s boyfriend Zygmund, after Renia[5] is executed by the Gestapo. The diary was chosen for its powerful description of the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland and the horrors of the Holocaust.

The approach to the document has deeply changed students’ perspectives and given them a more meaningful and insider understanding of the story.

The narration on the social account was not taken lightly, on the contrary: students seriously recreated the original context and the events as they were depicted in the diary; this effort did not trivialize or cheep the content’s acquisition but dramatically improved their analytical skills and the awareness of Holocaust atrocities the source evokes.

The whole experience was carefully supervised by the teacher in order to maintain a respectful attitude towards Reina’s inner world: the ability to visually transfer and assembly her memories through Instagram, augmented learners’ personal connection to Renia’s feelings, introducing a new environment to commemorate, save and store her story.

Conclusions

All the learning practices described so far, exemplify new multimodal re-enactment techniques for actively approaching Holocaust narratives.

The realized projects emphasized the students’ role as participatory recipients and co-authors of multifaceted content created from primary sources.

The 3D spaces, the interactive map, and the Instagram account arranged by students on the basis of the testimonies expanded their Holocaust experience making it multi-layered and interactive.

The students creatively remixed and adapted resources by supplementing the original texts with additional elements, in this way, they personalized their encounter with the Holocaust memories but without misrepresenting them.

We are aware that this use of resources, combining factual learning with creative and emotional responses, presents both chances and limits; however, providing students with the opportunity to retell personal Shoah histories in multiple digital formats, had the great potential to enable learners closer and detailed scrutiny of accounts and benefitted them with new and stimulating possibilities to engage with the past.

[1] Joseph Joffo, A bag of marbles, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974).

[2] Alexandra Zapruder, Salvaged Pages: young writers’ diaries of the Holocaust, (Yale: Yale University, 2004).

[3] Petr Ginz (editor Chava Pressburger), The diary of Petr Ginz, (London: Atlantic Books, 2007).

[4] Eva Heyman (editor Agnes Zsolt), The diary of Eva Heyman child of the Holocaust, (New York: Shapolsky Publishers, 1988).

[5] Renia Spiegel, A young girl’s Life in the shadow of the Holocaust , (London: Ebury Press, 2019)